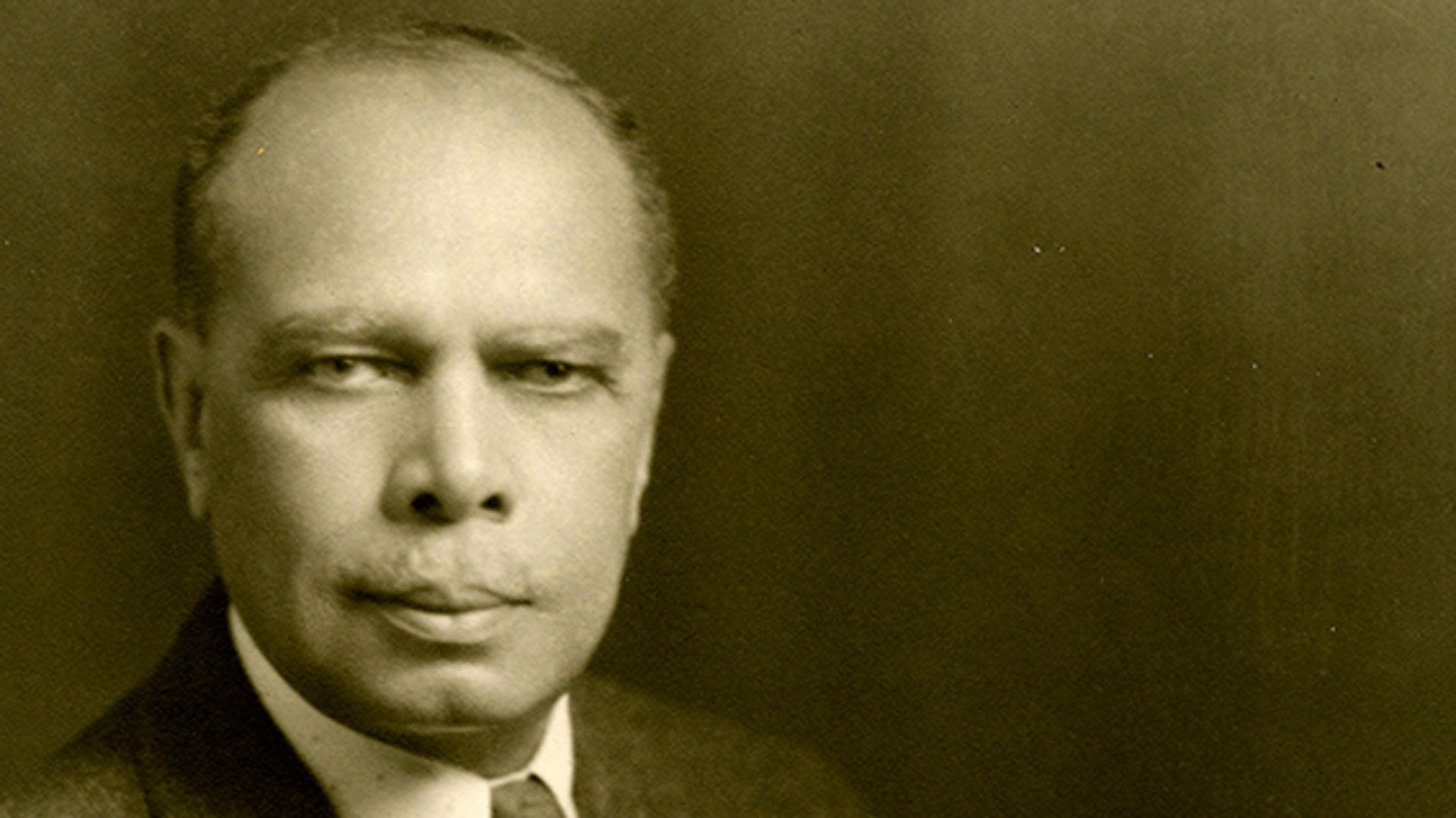

About James Weldon Johnson

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1871, James Weldon Johnson’s life was defined by a number of firsts. Educated at Atlanta University, he was the first African American to pass the bar in Florida during his tenure as principal of Stanton Elementary School, his alma mater.

A Man of Many Firsts

He also was the first African American author to treat Harlem and Atlanta as subjects in fiction in his genre-crossing novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man (1912).

As a scholar of African American literature, Johnson edited The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), the first anthology of African American poetry in English, and for decades a standard text in both English and African American Studies.

A pioneering ethno-musicologist, Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson, his brother and fellow composer, compiled and edited The Book of Negro Spirituals (1925), the first of a two-volume collection of Black sacred songs framed by a jointly authored introduction that traces the genesis and significance of one of the earliest Black art forms in the Americas.

Johnson also was the first African American poet to adapt the voice of the Black folk preacher to verse. These poems are gathered in his masterful collection of folk sermons in verse entitled God’s Trombones (1927), one of three collections of verse by Johnson.

The Author and His Achievements

A race man and an American with broad intellectual interests, Johnson also is the author of Black Manhattan (1930), a history of African American life and culture in New York, and Along This Way (1933), an autobiography. Johnson distinguished himself in civil rights, diplomacy, education, journalism, law, literature, and music.

His many impressive achievements notwithstanding, his place in African American history and culture would be secure if he had composed only in 1900 with J. Rosamond Johnson “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” a hymn officially adopted by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and widely sung by African Americans as the Negro National Anthem.

Multiple Languages

Admired for his able, judicious, and creative approach to leadership in an era stained by virulent forms of racism, Johnson, fluent in Spanish and French, was the first African American to serve as the United States consul to Venezuela and Nicaragua.

After his period of service in the consular corps, in 1915 Johnson joined the staff of the NAACP. Rising quickly through the leadership ranks, a year later he became the first African American to serve as field secretary and later as executive secretary of the NAACP. As executive secretary of the NAACP, Johnson organized in Manhattan the historic Silent March of 1917 (above) to protest the national crime of lynching.

During his tenure as executive secretary of the NAACP, Johnson also led a national campaign against lynching that garnered significant congressional support in the form of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill of 1921, a bill that would have made lynching a national crime, but it failed to become law because of insufficient votes in the Senate.

Other significant achievements during Johnson’s tenure as head of the NAACP include the exposure of the brutality of the Marines during the United State’s occupation of Haiti, and the national campaign to support the Houston Martyrs: the soldiers of the 24th U.S. Infantry sentenced to death or life imprisonment for the 1917 uprising in Houston, Texas.

Fisk University

After retiring from his position as head of the NAACP in 1930, Johnson joined the faculty of Fisk University as the Adam K. Spence Professor of Creative Writing. In 1934 he accepted an appointment as Visiting Professor of Creative Writing at New York University, thus becoming the university’s first African American faculty member.

A Remarkable Life with a Tragic Ending

Johnson’s productive and multi-faceted life ended tragically when he was killed in an automobile accident in the summer of 1938 while vacationing in Maine.

Born in the south but a figure of national and international significance, Johnson’s richly lived life marked by remarkable accomplishments, service and leadership merits its own living memorial.

Emory’s James Weldon Johnson Institute for the Study of Race and Difference is an intellectual project that seeks to capture and reflect the many artistic, scholastic, and humanitarian achievements of Johnson by supporting research that focuses upon the ongoing quest for universal civil and human rights.